Let me share a few observations about drawing. Although these insights are based on my experiences drawing in my sketchbook, they are general and apply to lots of creative activities, for example someone working to improve their cooking skills or master the trombone. Let’s see if you agree.

1

Effort. As a general rule, achieving quality requires effort. These two are roughly correlated—more quality typically requires more effort. So far, I know of no way to reliably improve quality by doing nothing. (But if you know that secret, I’d be interested. Please write.)

2

Diminishing returns.Often, early efforts produce significant progress but gradually it requires more and more effort to improve quality. In some sad cases, additional effort can actually reduce quality. That’s what happens, for example, when I overwork some detail in a drawing and the image becomes murky and less clear than initally. That’s always a sure sign to stop.

3

Take a break. When returns seem to be diminishing, it can help to step away from the project temporarily. Perhaps during the hiatus I can work on some other project. Later, when I come back to the original effort, I see things in a fresh way and it’s possible to make rapid progress again.

4

Chasing the horizon. Sometimes, returns don’t appear to diminish (2) and more effort continues to produce more quality. You keep working and the quality keeps getting better. This is dangerous territory because it could go on forever. You could continue improving to infinity—refining your drawing, tweaking your chocolate-chip cookie recipe, or polishing your trombone solo until the end of time. Is that really how you want to spend eternity?

5

Lost opportunity cost. Depending on your attitude about work, your efforts could be drudgery or delight. But even if you are having fun, working forever on one sliver of perfection has a hidden cost. While you are working on perpetually perfecting your chocolate-chip cookie recipe, you can’t be improving your chili recipe...or anything else. It is, therefore, wise to avoid being an unlimited perfectionist and to know when to stop.

6

Stopping perfection. The first, proven method to limit the unending quest for perfection is to limit your effort. The most popular limit is a deadline. With a deadline, you allow yourself to work as hard as you want to achieve perfection but you stop on Tuesday—some pre-defined point in time when you have promised to put down your tools. You can also limit effort by limiting resources. For example, I promise I will stop drawing when this sketchbook is full or this bottle of ink is empty.

7

Adequate. The second way to escape an infinite effort to reach perfection is to define an acceptable level of quality and stop when you reach it. For one of my drawings, I might require that it be clear, beautiful, and funny. Once those criteria are met, I can stop. For your chocolate-chip cookie recipe, you might define quality as “better than Aunt Betty’s” and stop when you reach that.

8

Where is good enough? I’m free to set the acceptable-level-of-quality threshold very high. I’m also free to raise this threshold on future projects as my skills increase. But, for a specific project, you don’t want this threshold to drift very much in either direction. Define it and stick to it.

9

Two limits. You can use both limits at the same time. I mean you can stop when you reach EITHER the deadline OR your defined level of quality.

Here’s a tip that might help you if you are eager to improve your skills. If you reach the deadline first, stop. But if you reach the acceptable-quality threshold well before the deadline and you are not experiencing a feeling of diminishing returns (2), it might be wise to continue working a little longer just to see what will happen. You might learn something you can apply on future projects or experience a major breakthrough. You never know.

10

Serendipity. Sometimes an accident will increase quality without me making much of an effort. I might momentarily lose control of my brush or absently draw some detail at the wrong scale and be unexpectedly rewarded with a pleasant result. I cherish these happy accidents.

The catch? There are three. First, happy accidents only happen when you are actually working. I can leave my drawing materials out for a week, but nothing magical ever happens until I actually start working.

Second, you must pay attention as you work to notice when good luck strikes. If you are not alert, you will miss it.

Finally, when good luck strikes and a new, unexpected path opens up, you must be willing to get off of your original path. Letting go can be surprisingly difficult, especially if you have been on that original path for a long time.

I hope these ideas help you. Let me know if you think they are true or not.

Don, Pittsburgh, March 22, 2017

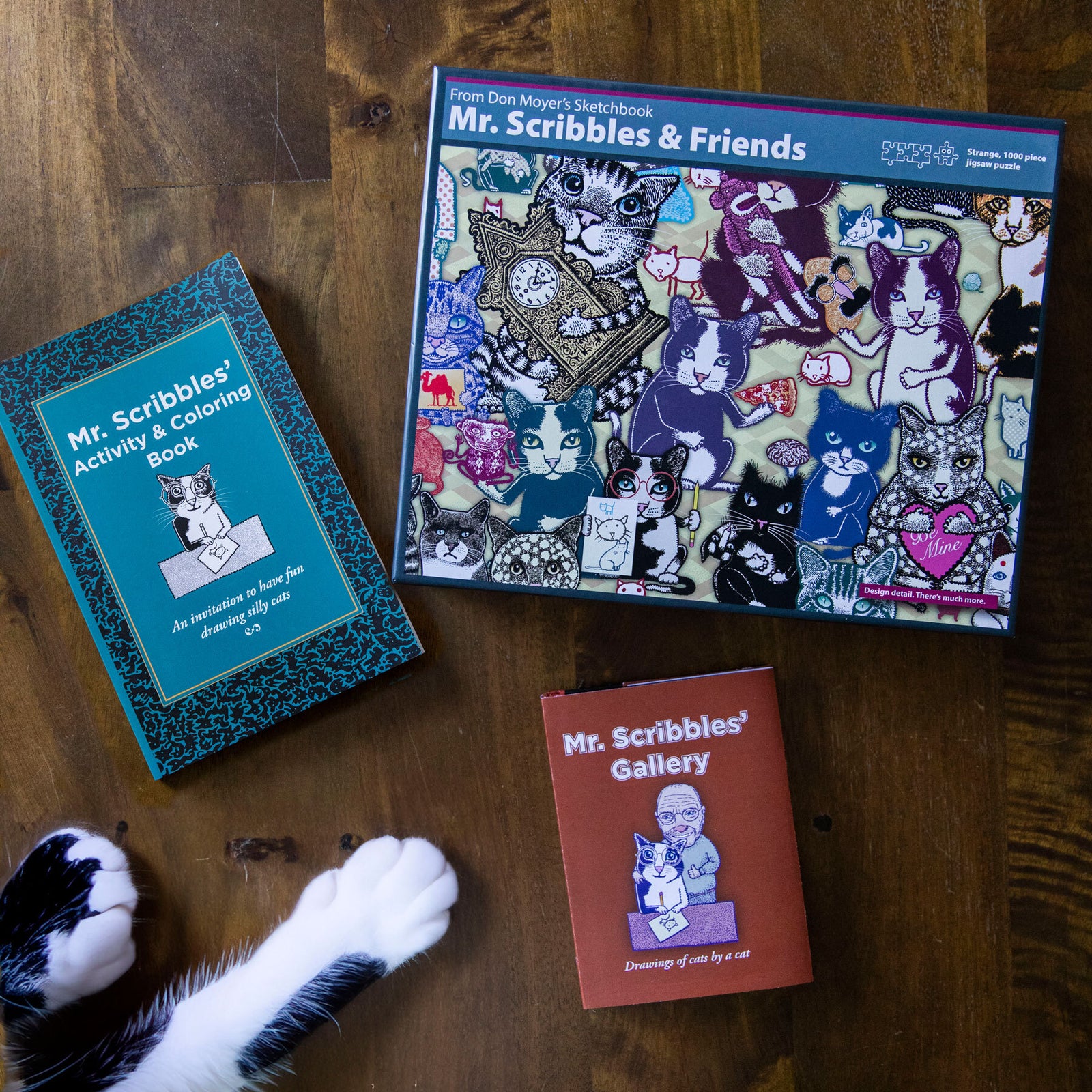

PS: My current Kickstarter project—Omnivore Bowls—is Active until April 7.

Bob Eames

March 26, 2017

Nice post Don!

The graphs reminded be how much I miss Panel Discussion and reminded me of your excellent work for us back in my furniture days.

I especially enjoyed your thoughts on setting deadlines. It reminded me of something that Ralph Caplan wrote as a tribute to Charles Eames in a piece published by Herman Miller entitled Doing Quality. A good reminder that doing your best is always subject to constraints and is not the same as perfection.

Here’s the excerpt you reminded me of:

This is not to say there were no deadlines to meet. There almost always were. But deadlines, like other constraints, were never to become excuses for inferior work. When describing the speaker he designed for Stephens Trusonic, Charles explained, “It was a matter of the best you could do between now and Tuesday.” However he was quick to add that “The best you could do between now and Tuesday is still a kind of best you can do.”

Now that my hiatus from work is through, I better get busy, my deadline is at hand and I hope I see things with fresh eyes ;-)

Cheers,

Bob Eames